That time we considered the dark side.

We've all been there. Your "free trial" insists on a credit card number. The X in the upper right hand corner meant to exit the annoying nag screen actually launches a sign up process. You check your cart after checking out and somehow you've been charged for a service you didn't add. And we all react the same way - screaming thinly-veiled obscenities at the screen as if the developers and designers can actually hear us and feel the burning coals we are heaping upon their heads (or maybe that's just me).

As a designer, I find these types of interactions particularly obnoxious because I know that someone somewhere created them deliberately. Make no mistake - dark patterns (designs that take advantage of your cognitive biases to manipulate you or deceive you) are intentional devices, not accidental bad design. And they are everywhere - some to such a degree that we take their presence for granted and even accept that "that's just the way it is." But that is starting to change.

In 2022, multiple lawsuits brought by the Federal Trade Commission against companies using dark patterns (such as fees hidden behind required scrolling, falsely routing people to sales sites, and making cancellation of services nearly impossible) resulted in fines of tens of millions of dollars. In March of this year (2023), consumers sued Audible due to free trials that converted to paid subscriptions without notice.

In June, the Federal Trade Commission sued Amazon over the onerous process needed to cancel subscription (a pattern often referred to as a "roach motel"). In the same month, they settled a lawsuit with Publishers Clearinghouse resulting in a UI overhaul to address manipulative design patterns. Recently, India outlawed the use of thirteen dark design patterns, in an update to the consumer protection act, and included language that would make room to outlaw more.

Dark patterns are designs that take advantage of your cognitive biases to manipulate you or deceive you, as demonstrated in this image from TechCrunch.

While there's definitely a lot of work to be done in this area, these laws are a start to raising awareness of how design can manipulate people into undesired and harmful actions by exploiting their cognitive bias'. A cognitive bias is our tendency, as human beings, to be bad at making objective decisions. We are creatures of emotion, and that emotion strongly affects our ability to make good decisions. There are many cognitive biases, and each can be used to influence our experience for good or evil. In this and our following blog posts, we'll take a look at each of the thirteen outlawed dark patterns and the cognitive bias' that are at work, as well as how to ensure you're avoiding them (preferably at the design system level).

False Urgency

“Only 3 left! Selling fast!”

“Most Popular Item - limited quantities”

Messages and designs falsely suggesting that a product will soon be gone if the buyer doesn’t act quickly, plays to Action Bias (our preference to do something rather than nothing) and Scarcity Bias (the harder it is to get something, the more we value it). We are afraid we’ll miss our opportunity and make purchase decisions impulsively, not reading through the details - basically it's FOMO in your shopping cart.

A great example of this is a garden ornament I purchased. It was absolutely adorable - a T-Rex dinosaur wreaking havoc on a bunch of garden gnomes. "Only 1 left!" I hurriedly added it to my cart and checked out...failing to check the size. My imagined tyrant of the garden arrived at a scant six inches in height. My broccoli was unimpressed, as was I. If I had taken a moment to read the dimensions of the tiny terror, I would have realized it's diminutive size and passed. But the urgency I felt to purchase it before the seller ran out overcame my usual due diligence. Avoiding false urgency is fairly straight forward - don't lie about the quantity of something you have or use language to imply a shortage or false importance.

There was only 1 left!

Gnome eating T-Rex, still awesome, but not as awesome as expected.

Basket Sneaking

You complete your checkout and notice that the total is five dollars more than you expected. After looking at the receipt, you see that a donation to Save the Houseplants foundation appears at the end. You don't remember adding it, but if you go back through the workflow you see there's a checkbox for the donation that you failed to uncheck. This pattern is known as Basket Sneaking - adding items to the total purchase without the user’s consent, including providing a default opt-in for services, donations, and subscriptions. This pattern also covers automatic opt-ins for marketing campaigns, emails.

This pattern plays to our Attentional Bias (our tendency to focus on certain elements and ignore others). By placing the checkbox at the end of a lengthy checkout, the user is less likely to notice it and by defaulting to "opt in" that lack of attention causes them to provide permission for something they may not want. A large percentage of the emails in my overloaded inbox are due to patterns like this - because while I may have noticed the opt-out the first time I purchased something from a website, chances are good I forgot to be on the look out for it the next time and I'm suddenly inundated with marketing emails for something I just purchased (seriously, how many copies of "DIY Garden Gnomes" do I need?) To avoid basket sneaking, provide optional things like subscriptions and add-ons early on in the checkout process and ensure they are NOT selected by default.

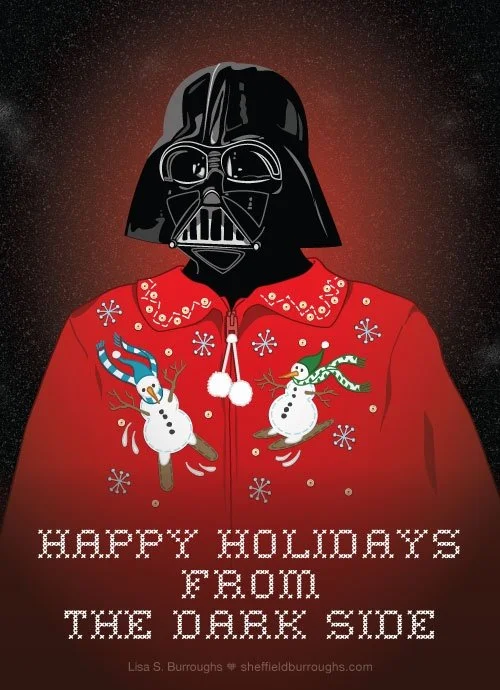

In our next blog post, we'll talk about Confirm Shaming, Forced Action, and Subscription Traps. Until then, remember to use your powers for good and may the Force be with you.

(Happy Holidays!)